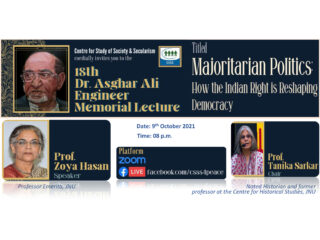

Justice A. P. Shah delivered a memorial lecture in memory of late Justice Hosbet Suresh titled “The Supreme Court in Decline: Forgotten Freedoms and Eroded Rights” on 18th September, 2020. The lecture was organized collectively by Centre for Study of Society and Secularism, Bohra Youth Sansthan, Central Board of Dawoodi Bohra Community, Citizens for Justice and Peace, Institute for Islamic Studies, Peoples’ watch and Majlis Law centre. The Lecture was chaired by senior Advocate Dushyant Dave, President, Supreme Court Bar Association. The Dr. Asghar Ali Engineer Lifetime Achievement Award was conferred posthumously on Justice Hosbet Suresh during the event. In the lecture, Justice Shah took the audience through the role of Supreme Court in different times and problematized its role in the recent times.

Below is the full text of Justice A. P. Shah’s speech

Introduction

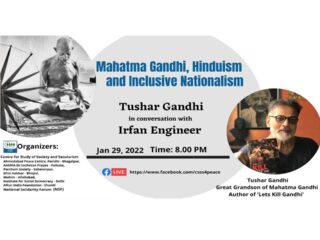

Good evening to all of you present here today. I would like to extend my thanks to Mr. Irfan Engineer for having organised this event, and invited me to be a part of it, and am delighted to be sharing the same space with Mr Dushyant Dave.

When Mr Engineer informed me that Justice Suresh was going to be posthumously awarded the Dr Asghar Ali Engineer Lifetime Achievement Award, it struck me that there could be no better person for this recognition.

I was fortunate to have met Dr Engineer once, and of course, known and appeared before Justice Suresh several times. Both men were similar in many ways. Both were activists in their own right. Dr Engineer was a reformist, and fought for change in the Dawoodi Bohra community, and his valuable contributions to studies in peace, non-violence and communal harmony are well-regarded. Equally, Justice Suresh was known, especially in his three decades of public life after retirement, for his path-breaking contributions to the human rights space. Wherever there were instances or occasions of human rights violations, Justice Suresh’s wisdom, presence and support always made an appearance.

The commitment of Dr Engineer and Justice Suresh to their causes and what they identified as their life missions was unshakeable. Even in the face of physical and verbal attacks, which both men had to face to varying degrees, they continued to stand up tall, perhaps aware that their display of such courage under fire was necessary to set an example for ordinary people like us to keep fighting for just causes. Justice Suresh said that ‘his voice was his conscience’, which was also the title of a book he wrote. This applies to Dr Engineer in equal spirit. I would say that both their voices were the conscience of the nation, and we should be ever grateful to them for showing us all the path.

The Supreme Court’s Glorious Past

It is in this same spirit that I speak here today of what I believe is one of the most troubling developments of our time: the decline of the Indian Supreme Court. As a former judge, at the very least I believe it is my duty to ring some warning bells.

The political thinker, Edmund Burke, said that judges are trained so that they can detect misgovernment, and especially, “sniff the approach of tyranny in every political breeze”. This is the kind of Court we need, but unfortunately this is not the Court we have right now.

The Supreme Court has had a glorious past that it should be proud of. The statesmanship that the 13-judge constitutional bench exhibited in the decision in Kesavananda Bharati, where the basic structure doctrine was laid down, and judicial custody of the Constitution reclaimed, is but one shining example of what the Court is capable of. Indeed, Granville Austin said that the Court had established itself as “the logical, primary custodian” of the Constitution, and “its interpreter and guardian.”

The Supreme Court started out as a passive court. Slowly but surely, as the institution understood its role in the governance of the nation, it expanded its authority, thus laying the foundation for an activist role in future. Kesavananda Bharati was the start of all this. Over the years, there were many judgements that cemented the Supreme Court’s identity further. Notable amongst these were Maneka Gandhi, Frances Coralie Mullin, and International Airports Authority, where, variously, due process was introduced, and there was an expansion of the rights enshrined in Article 21 of the Constitution.

The “invention” of the public interest litigation marked the beginning of what has been termed the “socialist judicial” era, where the Court’s activist role came into prominence. In the late 1990s, it expanded its scope into relatively less-explored territories, such as environmental protection, using its powers to tackle important questions in that arena. In doing so, it also entered the domain of the executive, and was roundly criticised for this. This criticism is not unwarranted, and indeed, even though it has its advantages and there is a tendency to praise the instrument, the PIL has been abused on some occasions. But this is not the place to talk about this.

It is not as though the Supreme Court did not have its ups and downs. Most notoriously, in the ADM Jabalpur case, there was a moment of realisation that the Court had gone astray, and the years that followed were doggedly spent in restoring some respectability to the institution. The 1980s and 1990s reversed its reputation, and for a brief period, it seemed as though the Supreme Court had returned to being the sentinel on the qui vive, which the first generation of judges had hoped it would remain. Now, however, we seem to have regressed once again, and desperately need a wake up call in order to avoid another Emergency-like disaster.

An overpowering executive

You may well ask why this is all relevant. On paper, we have a liberal, democratic, secular republic with all its wheels in place. We have fundamental rights tightly ensconced behind seemingly impenetrable firewalls. With a parliamentary system of government, separation of powers, and a federated division of responsibilities between the centre and states, we have a system that is the envy of many. On paper, the all-powerful executive is held accountable to the people through the legislature; and to the Constitution and the rule of law, through the judiciary; and through other institutions like the auditor-general, the election commission, a human rights watchdog, and anti- corruption bodies, besides entities like the press, academia, and civil society. Unfortunately, remember what I said – this is all only on paper.

In India today, every institution, mechanism or tool that is designed to hold the executive accountable, is being systematically destroyed. This destruction began in 2014 when the BJP government came into power. There is a temptation to compare this with the blatant destruction that the Indira Gandhi government indulged in the past, but comparisons are odious. What we are witnessing today is a force in action strategically intending to render the Indian democratic state practically comatose, with all the power entrusted with the executive.

Besides the various limitations of Parliament that have been revealed in recent times, it has not even met during the Covid-19-induced lockdown, and even when it finally decided to meet, question hour has been scrapped. Even if Parliament has been debilitated, other entities should have stepped up to the plate and kept the executive in check. We have heard nothing of the Lokpal since forever. The National Human Rights Commission is dormant. Investigation agencies are misused at the slightest opportunity. The Election Commission of India appears to have been suspiciously compromised. The Information Commission is almost non-functional. The list is long and troubling. Even academia, the press, and civil society have been systematically destroyed or silenced. Universities are under attack daily, whether it is students being accused of rioting, or teachers being accused of criminal conspiracy. The idea of an unbiased mainstream fourth estate in India died its death a long time ago. And civil society is being slowly but surely strangled, through various ways.

But the most worrying of all is the state of the judiciary. There are many important issues that need to be deliberated upon today. With Parliament already so weakened, the Supreme Court would have been the next best space to discuss the Kashmir trifurcation, the constitutional validity of the Citizenship Amendment Act, suppression and criminalisation of protests against this law, misuse of draconian laws like sedition and the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act, electoral bonds, etc. Sadly, most of these are ignored or brushed aside or mysteriously kept pending for an indefinite period of time. We might not be in a state of war, but we are in a state of emergency, unprecedented for generations. Central to all this, and certainly, of most concern to me, is the role of the Supreme Court.

Start of the Court’s decline

In my view, the start of the Court’s decline coincided with the coming to power of the BJP-led NDA government in 2014. No one will deny that the NDA government swept in a new political wave, an ideology that was less centrist than we were accustomed to in the previous years, and arguably, far more right-wing than what it had exhibited in its own previous avatar. The Supreme Court’s descent was not fortuitous or coincidental, but was part of a larger, deliberately-crafted strategy on the part of the executive to seize control of the arms of the state, in ways that would benefit its own political agenda.

There was an immediate confrontation upon the NDA taking over, in the form of the constitutional validity of the National Judicial Appointments Commission Act in 2015. The Court, in a bold display of independence of spirit, struck down the legislation. Indeed, the Court’s engagement with the newly-appointed government of 2014 onwards began very well. The Court mostly stood its ground against the executive, and shone particularly brightly in matters of judicial appointments. But this is, sadly, all gone today.

We know that the appointments of new judges and transfers of existing judges across high courts many a times are decided, or even arguably, orchestrated, by the Law Ministry. Recent instances of the transfers of Justices Akil Qureshi, Muralidhar, Jayant Patel, were all eminently questionable, but the Court did not utter a word and quietly allowed the judges to be relocated. All of the bombast about fiercely protecting independence expressed in the NJAC case seems to have been thrown to the wind.

There was a brief watershed moment with the January 2018 press conference, where four Supreme Court judges, in an unprecedented move, went public with their grievances over matters of judicial administration and management. There were also some sparks of self-expression shown occasionally, as in the right to privacy discussed in Puttaswamy, or the Shreya Singhal case, where Section 66A of the Information Technology Act was struck down – the first time a law was struck down for violating Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution, or the decriminalisation of homosexualiity, or recognising transgender rights, or the many cases pertaining to gender justice, such as those on adultery, triple talaq, and promotion in the armed forces. Note, however, that – with the exception of Section 66A – the executive is really not concerned about these issues. But wherever the executive is an actively interested party, and wants to undermine the rights of the people – usually in order to further its own realpolitik agenda – you will find that the Court is being pushed to the wall.

The Court’s proclivity to buckle in submission in matters where the executive takes a stand has not gone unnoticed. A news report by the Indian Express showed that of the recent ten most important judgements of the Supreme Court on free speech, only four were decided in favour of the person claiming the right to free speech. Critically, in all four of these cases, the government either supported the petitioner or expressed no objection. In contrast, wherever the government opposed, the cases failed. This is how the court seems to be turning in all matters.

The Court generally is becoming more prickly when it comes to issues of free speech, as evidenced in the most recent Prashant Bhushan case. In a display of self-proclaimed “magnanimity”, the Court let off Mr Bhushan with a fine of one rupee for the contempt case against him over two tweets, but not without chastising his conduct. In the entire proceedings, one thing was clear: the Court came across as an intolerant institution.

The truth is that the era of the Supreme Court’s glorious jurisprudence has all but vanished. We seem to have only memories of its illustrious past to reminisce upon today. We were recently told in Puttaswamy case that the ghosts of ADM Jabalpur had been buried deep, but I fear that these ghosts may have returned to haunt us once again.

Forgotten Freedoms

The most stark representation of the Court’s decline can be seen in its failure to perform as a countermajoritarian Court. I emphasise counter-majoritarianism because it is important to recognise the role of the Court in protecting the interests of minorities. A democracy derives its legitimacy from representing the will of the majority. But this legitimacy comes at a cost, which is invariably borne by minority groups, and especially those that are unpopular or victims of deep prejudice and who cannot influence the legislature in any way. This power to protect minorities from the tyranny of the majority is the basis of judicial review powers that allow Courts to strike down laws for violating the Constitution.

Now, though, it seems that the Court is turning away from decades of its own history, and is, instead, aligning with the majoritarian view unhesitatingly and without question. Two recent cases which demonstrate this clearly are Sabarimala and Ayodhya.

The original 2018 Supreme Court judgment in Sabarimala was an extremely progressive one: it permitted the entry of women into the Sabarimala Temple in Kerala. But when the Kerala state government tried to implement the Court’s judgment, the BJP-led centre sided with Ayyappa devotees. The Court’s word should have been final, but the Central Government seemed to believe that was not the case.

Soon after, review petitions were filed, but these were kept pending for certain referred questions to be decided by a larger bench. There was no stay on the main judgment. But the Court said that the referral meant that the judgement was “not final”, and therefore, refused to issue directions on a petition for seeking safe entry into Sabarimala.

This has opened up a pandora’s box of nightmares that we might live to regret: it means the Central Government can, with impunity, ignore the Supreme Court; and that judgments can be conveniently “re-opened” through referrals in the guise of reviews. What implications does this have for the rule of law?

The issue of rule of law and finality also came up in the Ayodhya judgment. In its unanimous but unusually anonymous decision on an essentially political issue, the Court said that the Allahabad High Court’s decision to divide the property into three parts was not “feasible” in order to maintain peace and tranquillity. However, did the Supreme Court’s judgment result in complete justice? Despite acknowledging the illegalities committed by the Hindus, in 1949 and 1992, the court effectively rewarded the wrongdoer. Surely, this is against the doctrine of equity, where one must approach the Court with clean hands.

Just as the central government exhibited impunity in the Sabarimala judgment, in the Ayodhya case, too, the Hindu Mahasabha pressed for the withdrawal of criminal cases against the kar sevaks involved in the 1992 demolition and violence. It also demanded that the kar sevaks be given government pensions, and their names listed in the temple on the site of Masjid! – as though they were freedom fighters! The Supreme Court has said that the criminal cases must continue, but in the larger scheme of things, I am doubtful if any meaningful result will emerge.

Constitutional commitments

The failure to remain committed to the Constitution, as demonstrated by the Court’s jurisprudence on Article 21, is becoming increasingly visible. In the face of the colossal public health crisis caused by COViD-19, the lives of migrant labourers have turned upside down: they have no work, no source of income, no access to basic necessities,and no means to reach home. Instead of taking on petitions questioning the situation, for the longest time, the Court refused to admit or adjourned these petitions.

In rejecting or adjourning these petitions, the Court made several questionable remarks: it said that governments already provided labourers with two square meals a day, so what more could they possibly need (surely, ‘not wages’); and that incidents like the horrific accident where migrant labourers sleeping on railway tracks were killed could not be avoided because ‘how can such things be stopped’.

Many of the so-called excuses of the Court have been tackled by previous judgements, notably the question of policy and non-judicial interference, for instance, the right to food; various environmental protection policies. In these cases, the Court formulated policies and asked states to implement them. In the migrant workers case, though, it made the unfortunate presumption that the government is the best judge of the situation. The suo motu recognition of the issue by the Court also came too late. Instead, the High Courts came across as islands of rationality, courage and compassion in these times, asking questions about migrant rights. Contrast this with the Supreme Court’s reaction to the bizarre claim of the Solicitor-General who argued that the exodus of workers was due to fake news: the Court accepted this, and media houses were advised to report more responsibly.

Our Supreme Court today, sadly, has time for a billion-dollar Indian cricket administration, or the grievances of a high-profile journalist, but studiously ignored the real plight of millions of migrants, who do not have either the money or the profile to compete for precious judicial time with other litigants.

Eroded Rights

Another kind of repression that is happening, perhaps unprecedented in modern India, is the stifling of the right to protest and to free speech. The executive is spearheading this, and the judiciary is either tacitly agreeing with the executive overtly, or maintaining silence around the issue. If we want to boast about being citizens of a democratic nation, this ought to be the first thing that worries us.

Take the protests against the clearly unconstitutional Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA). The constitutionality of the law was challenged in the Supreme Court, but the Court itself avoided taking up the matter for flimsy reasons. Meanwhile, the government has desperately tried to silence protestors. Indeed, the government is using every imaginable means, to silence any and all dissenting opinion, and to clamp down on any alternate views that might exist. More problematically, the judiciary is watching all this happen by the sidelines, like a mute spectator, without uttering a word.

Different strategies are employed in different states. In Uttar Pradesh, its Chief Minister said that he would take “revenge” against protestors, and that chanting “azadi”, or ‘freedom’, would amount to sedition! Police have been given license to run riot against peaceful protestors, by arresting them, destroying vehicles, and even entering homes. Targets tend to be young Muslims. A combination of charges under the National Security Act and the Goonda Act were used in UP.

But the burning issue in this context has surely been the Delhi riots. The government has been targeting those who express an honest view, and engage in honest protests, and even, on occasion, stage a play! Unarmed students have been attacked by the police. Anyone critical of the establishment, regardless of their intentions, such as Apoorvanand and Yogendra Yadav, are implicated at the slightest opportunity. The strategy in Delhi has been to charge individuals with criminal offences of rioting, unlawful assembly, criminal conspiracy, and that awful colonial legacy that is sedition, to name but a few, in conjunction with the (newly interpreted) Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA). Contrast this treatment of civilians with that of leading politicians of the ruling BJP who have publicly delivered inciteful speeches. Shockingly, no punitive action was taken against them. Instead, the one judge who showed some inclination to take action was conveniently transferred.

The arrests here have been to a template: if a person expresses a legitimate view against the CAA, he is promptly labelled an anti national, and the law enforcement machinery kicks in. It does not matter that the CAA is a blatantly unconstitutional law. The police says that the protesters sought to “execute a secessionist movement in the country by propagating an armed rebellion” in which “the anti-government feelings of the Muslims will be used at an appropriate time to destabilise the government.”

The former police officer, Julio Ribeiro, has pointed to the lack of a fair investigation in the Delhi riots, drawing similarities with the 1984 riots here. He rightly said that “riots recur in India because of the impunity accorded to one section by the political establishment of the day”. Police investigations in the riots have been based on mere “disclosures”, with no concrete evidence. Surely, this goes against all principles of fair investigation. By taking action against peaceful protesters, but deliberately failing to register cognisable offences against those making the hate speeches that triggered the riots in Delhi, the Delhi police has been accused of being partisan and politically motivated. With the police taking a majoritarian stance as well, effectively, the real culprits of the violence belonging to the majority community are allowed to get away.

Why are the political establishment, and the police so emboldened? Undoubtedly, it is because of the weak judiciary that we have in India today. Had the Supreme Court not remained a mute spectator, and had it intervened more proactively, all this would arguably not have happened. Instead, the Supreme Court conveniently declined to intervene, showing no urgency in wanting to deal with these problems. For weeks, the matters involving many of these issues (for example, the Delhi riots) kept getting adjourned. Even where matters were heard and decided, when they were appealed, there was judicial silence. When the Allahabad High Court directed that protestors’ photographs put on hoardings should be pulled down in 24 hours as the action was unsupported by law, in appeal by the UP government, the two-judge Supreme Court bench agreed with the High Court on the unlawfulness of the action, but it still mysteriously made a reference to a three-judge bench, effectively permitting the state to ignore the High Court order.

To make matters worse, the Supreme Court’s April 2019 decision in NIA vs. Zahoor Watali on the interpretation of the UAPA has affected all downstream decisions involving the statute. This decision has created a new doctrine, which is that effectively, an accused must remain in custody throughout the period of the trial, even if it is eventually proven that the evidence against the person was inadmissible, and the accused is finally acquitted. The illogic of this veers on the absurd: Why must an accused remain in jail only to be eventually acquitted? According to the decision delivered by Justice Khanwilkar and Justice Rastogi, in considering bail applications under the UAPA, courts must presume every allegation made in the First Information Report to be correct. Further, bail can now be obtained only if the accused produces material to contradict the prosecution. In other words, the burden rests on the accused to disprove the allegations, which is virtually impossible in most cases. The decision has essentially excluded the question of admissibility of evidence at the stage of bail. By doing so, it has effectively excluded the Evidence Act itself, which arguably makes the decision unconstitutional. Bail hearings under the UAPA are now nothing more than mere farce. With such high barriers of proof, it is now impossible for an accused to obtain bail, and is in fact a convenient tool to put a person behind bars indefinitely. It is nothing short of a nightmare come true for arrestees.

This is being abused by the government, police and prosecution liberally: now, all dissenters are routinely implicated under (wild and improbable) charges of sedition or criminal conspiracy AND under the UAPA. Due to the Supreme Court judgement, High Courts have their hands tied, and must perforce refuse bail, as disproving the case is virtually impossible. As a result of this decision, for instance, a High Court judge can no longer really adjudicate and assess the evidence in a case. All cases must now follow this straitjacketed formula of refusing bail. The effect is nearly identical to the draconian preventive detention laws that existed during the Emergency, where courts deprived people access to judicial remedy. If we want to prevent the disasters of that era, this decision must be urgently reversed or diluted, otherwise we run the risk of personal liberties being compromised very easily.

This abuse of the UAPA and constant rejection of bail applications of accused as a means of silencing opposing voices can be seen most in the Bhima Koregaon cases, where mere thought has been elevated to a crime. In this matter, involving the arrests of many individuals, the so-called evidence was a typed, unsigned, undated document already in the public domain, which was taken from the devices of Varavara Rao and Gautam Navlakha, and attributed to them. The document titled “Strategy and Tactics of the Indian Revolution” was referred to in a book published six years ago. This document is also publicly available online. There is no section 161 witness statement that has been relied upon in the matter of Sudha Bharadwaj. But as a consequence of UAPA being applied, the accused cannot even get bail. Courts cannot go into the merits of the case due to the Supreme Court judgement.

The pattern followed in these arrests are all very similar: social activists, academicians, public intellectuals, who have worked in certain parts of the country are first accused of Maoist conspiracies, then with charges of misguiding Dalits, and then under the UAPA.

Sudha Bharadwaj has been in jail for two years. Varavara Rao, a Covid-19 patient, is not allowed to get out and receive proper treatment. We hear of fresh arrests ever so often. Navlakha’s case is a classic example of how the High Courts are being discouraged from doing anything. Navlakha made an application for bail before a Delhi High Court judge, but when the matter was being heard, without informing the Court, Navlakha was transferred to prison in Mumbai. When the judge enquired as to how and why this was done, there was no response from the government. Instead of explaining its position to the High Court, the Solicitor-General took the matter to the Supreme Court, and the Court simply rejected the bail application, virtually ending the proceedings before the High Court.

Abdicating Justice

The next characteristic contributing to the Supreme Court’s decline is in the failure to perform its fundamental role as adjudicator itself. In the Kashmir case, it has practically abdicated its role as a Court!

The Court’s decision in the internet shutdown case (Anuradha Bhasin) was laudable in many respects, but failed to actually decide the matter. After ruling that the suspension of communication services must adhere to the principles of necessity and proportionality, the Court failed to apply these principles to actually decide the legality of the communication shutdown in Kashmir. In its decision of May 2020, instead of itself dealing with constitutional issues relating to Articles 14, 19, 21, proportionality and strict scrutiny, the Court merely upped and handed over the exercise, of “advising” the court and the administration on the applicability of Anuradha Bhasin in J&K and denial of 4G services, to an executive-led Special Review Committee.

This is clearly a case of misguided, and surely, constitutionally unacceptable, delegation: the executive has been asked to conduct a review of its own actions, when in fact the judiciary should have been conducting a judicial review of executive action. As expected, the Review Committee rejected the representation, leaving the entire J&K population without 4G services for an unforeseeable future (it has already been over a year!). Should this denial of the fundamental right and access to internet be ignored so unsubtly? To use Senior Counsel Arvind Datar’s phrase, this is a case of justice having been “outsourced”, which is arguably tantamount to justice being denied.

There is also a pattern of judicial evasion being followed by the Court in the Kashmir cases: when petitioned as to how the internet shut down was affecting the public health delivery system in J&K, the Supreme Court told the petitioner to approach the High Court to avail the appropriate legal remedy. The over 1.3 crore population of J&K is suffering, with health, education, business and economy all operating at a loss, because of the executive’s internet shutdown. The Supreme Court seems to simply not want to deal with real-world problems at all.

Contrast this with how other jurisdictions have dealt with conflicts between individual liberty and national security, as described by Mr Datar. In Liversidge v Anderson, Lord Macmillan famously observed that “The fact that the nation is at war is no justification for any relaxation of the vigilance of the courts in seeing that the law is duly observed.” After the September 11 attacks, the United Kingdom enacted a law to detain and deport non-UK citizens, if there were suspected terror links. The law was struck down in A v. Secretary of State for the Home Department, on grounds including discrimination, with the courts drawing a distinction between the subject of national security being a matter of political judgement of the executive and Parliament, and the issue of whether individual rights were violated being the subject for judicial scrutiny. Elsewhere, the US Supreme Court struck down the government Military Commission for trying detainees at Guantanamo Bay for violating the Uniform Code of Military Justice and the Geneva Conventions in Hamdan v Rumsfeld. Note that Hamdan was Osama Bin Laden’s chauffeur, but the Court did not flinch. Similarly, when the Iranian Bank Mellat was suspected to be funding entities supporting Iran’s missile program, and the UK Treasury issued a directive prohibiting dealings with the Bank, the UK Supreme Court, in Bank Mellat v. Treasury, revoked the directive for failing to balance the rights of the bank and the interests of the community. Surely, the Indian Supreme Court should have taken a leaf out of the books of its peer institutions in the US and UK, and applied its own mind in such matters.

Master of the roster

That the judiciary is failing spectacularly to remain an independent institution is evident. That the executive is in fact responsible for this is also an open secret. How the executive is doing this is also well known. There is no need to expend energy in packing the Supreme Court with pro-government judges. Finding over 30 judges who think alike would anyway be difficult, if not impossible. The combination of opaque systems like the “master of the roster”, and a certain kind of Chief Justice of India, and a handful of “reliable” judges, is sufficient to destroy all that is considered precious by an independent judiciary. Of course, this is far from being a hypothetical scenario, and is, in fact, playing out in India right now. The truly independent and competent judges in the Court have been relegated to adjudicating private disputes, and are considered inconsequential. Many commentators have already pointed out how the last three CJIs all used the powers anointed upon themselves via the “master of the roster” to entrust politically sensitive and important matters to benches involving the recently-retired Justice Arun Mishra.

There is a tendency to view the threat to judicial independence in India as emerging from the executive branch, and occasionally the legislature. But when persons within the judiciary become pliable to the other branches, it is a different story altogether. Today’s situation was foreseen many decades ago by Chief Justice Y.V. Chandrachud, when, in 1985, he observed, “There is greater threat to the independence of the judiciary from within than without…” All the sermonising in the world is of no use without any real changes in the way things work.

How democracies die

In their book titled, How Democracies Die, Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt, write of how “most democratic breakdowns have been caused not by generals and soldiers but by elected governments”. They document the many instances of how “elected leaders have subverted democratic institutions” across the world. This subversion is carried out by the constitutional sanction of the ballot box, and even with approval from the legislature and the judiciary. Throughout, there is always the assurance that the democractic wheels are still turning. Levitsky and Ziblatt call the leaders who thrive in such situations “elected autocrats”. Such elected autocracts weaponise institutions, to use them as political ammunition. They compel the media and the private sector into silence, and they redraft rules to suit their interests over those of their political opponents. Critical voices still rise up in the backdrop but those who dare to question the powers that be end up at the receiving end of all kinds of trouble – they are charged with making seditious remarks, or evading taxes, or some such thing. In this way, they use “the very institutions of democracy … to kill it”.

To put it bluntly, this is what is happening in India today. In the face of all this, the one institution which has the capacity to turn the tide is the judiciary. Unfortunately, it seems to have lost its way. There was a period in history, during the Emergency, as well, when the Supreme Court failed the nation, but it realised its follies and returned to its natural path in course of time. Now, too, we have many judges and exemplary lawyers in practice who are sincere and committed to constitutionalism and to the rule of law. I expect they will rise to the occasion. The occasion is now. More than 70 years ago, in the Constituent Assembly, Nehru had said that we needed judges of the “highest integrity”, who would be “[persons] who can stand up against the executive government and whoever might come in their way.” I am hopeful that we will once again be able to see judges like these thrive in India.

***