Irfan Engineer and Vineeth Srivatsava Bhagyanagar

CSSS would be studying communal violence in Meerut (UP). Towards that, the authors visited Meerut on 13th October 2021 and talked to some lawyers representing the survivors of the communal violence to understand the situation. We would be visiting again to talk to the survivors and various stakeholders and reporting. This is the first in the series – editor.

According to answer given by Ministry of Home affairs in parliament in response to question about the rise in the incidents of communal violence in India, the year 2017 saw 822 incidents of communal violence. Uttar Pradesh is at the top in the table accounting 44 deaths and 540 injuries only in 2017. Apart from Uttar Pradesh, states like Rajasthan, Jharkhand and Bihar also witnessed increase in communal violence in 2017. The actual number of incidents and fatalities would be much higher since many cases go unreported.

Background of Meerut:

Situated between rivers Ganga and Yamuna, Meerut is a busy trade centre of Western Uttar Pradesh, about 70 kms from Delhi and falling within the National Capital Region. According to the 2011 census, the Meerut Urban Agglomeration (Meerut UA) has a population of around 1.42 million, with the municipality contributing roughly 1.31 million of it. The Meerut Urban Agglomeration consists of area falling under Meerut Municipal Corporation, Meerut Cantonment Board and 4 census towns of Sindhawali, Amehra Adipur, Aminagar and Mohiuddinpur (Wikipedia (a), 2021). Meerut city which had a population of over five lakhs in 1984, Hindus were 51 percent and Muslims were about 49 percent (Engineer, 1984, p. 271).

There are five assembly constituencies under the Meerut Lok Sabha constituency (Wikipedia, 2021). The Indian National Congress was first defeated in the year 1967 by Samyukta Socialist Party candidate and since 1967, Congress could win only 4 times. Amar Pal of the BJP represented the constituency from 1994 to 1999, winning the Lok Sabha elections thrice during the period. Avtar Singh Bhadana of Congress, belonging to Gujjar caste, represented the Constituency from 1999 to 2004. Bhadana has also represented BJP from the Meerapur Assembly Constituency. Mohammed Shahid Akhlaq of BSP represented the constituency from 2004 to 2009. Since 2009, Rajendra Agarwal of the BJP has been representing the constituency by winning elections in 2009, 2014 and 219. The runner up in 2019 was Haji Yaqoob Qureshi of BSP, who lost by less than 5,000 votes. If the votes polled by the second runner up is added, BJP would have lost the seat. Even in the 2014 general elections, if the votes polled by the three Muslim candidates belonging to BSP, SP and INC are added, the BJP candidate would have lost from the constituency. The Meerut Lok Sabha constituency has five Vidhan Sabha segments and four of them elected the BJP and in the 5th, Samajwadi Party candidate Haji Rafiq Ansari was elected. From the foregoing, it can be concluded that in order to win elections from Meerut Lok Sabha and Vidhan Sabha constituencies, the BJP has to politically mobilize the Hindus and at the same time divide the Muslim votes. The BSP poses a potential threat to the BJP as it has the potential to mobilize the Dalit votes as well as Muslim votes. During the 1982 communal riots, in which 90 Muslims and 10 Hindus died, the BJP was making a conscious attempt to woo the Dalits (Engineer, 2004, p. 63). In 1982, the MP as well as MLA from Meerut were Muslims – Mohsina Kidwai and Manzoor Ahmad – both belonging to the Congress, which had it social base among the Muslims as well as Dalits. The BJP actively wooed the Dalits from Valmiki community, and their ex-MLA Mohanlal Kapoor would participate in the puja of the community from a distance. In the 1982 communal riot, Dalits were successfully mobilised to attack the Muslims through rumours about an imminent attack from Muslims, which caused insecurity and apprehension among them, as well as by offering financial and material incentives.

The city has its importance in as much as the 1857 rebellion commenced off from the city. Meerut city is one of the largest producers of sports goods and musical instruments in India. The traditional industries in the Meerut city are handloom and scissors. Muslims mostly worked as weavers and some even owned looms. The cloth produced was sold to the Hindu traders. Muslims are also engaged in production of scissors and brass bands, in which they enjoyed a monopoly. While most Muslims in Meerut are poor, many of those engaged in brass band manufacturing units are prosperous. Engineer (1984, p. 272) noted that all the ingredients that resulted in communal riots were present in Meerut – 1) middle-sized town, 2) high proportion of Muslims, more than 30%, 3) a well-to-do section amongst the Muslims that could be potential competitors of Hindu traders, 4) political competition between the elite. The 1982 riots lasted for more than four weeks.

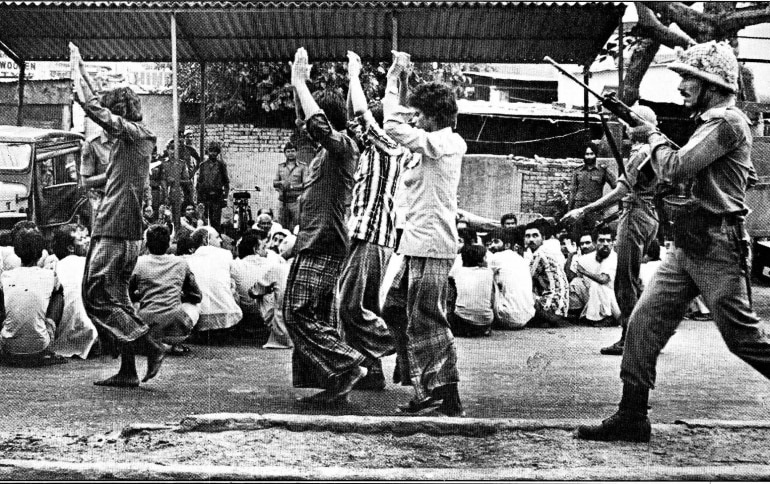

According to 2011 census, Meerut district population stands at about thirty-four lakhs. Of which, Hindus account for 63.40 per cent of the population and Muslims about 34.43 per cent. People practising Christianity, Buddhism, Sikhism, Jainism and other faiths are less than two per cent of the total population of the district. Meerut has been a site of endemic Hindu-Muslim riots (Brass 2004). Some of the serious riots which resulted in death occurred in 1939 and 1946 pre independence and 1961, 1968, 1973, 1982, 1986, 1987, 1989, 1990 and 1991 post-independence. Ashutosh Varshney and Steven I. Wilkinson (1996) note that Meerut ranks very high in the list of ‘riot prone towns’ in India during the period of 1960-1993. 17 people were killed in the 1968 riots that were triggered by attack on a political meeting of Muslims by the Hindus (Engineer, 2004, p. 38). The 1973 riots started over an argument between a Hindu shopkeeper and his Muslim client. Nine persons died and 40 persons were injured in that riot (Engineer, 2004, p. 45). The 1982 riots were major riots in which 100 persons were killed (90 Muslims and 10 Hindus); 53 Hindus and 27 Muslims were injured. The PAC bullets killed 42 of the 90. Lot of ammunition, including 10 country made revolvers, 28 bombs, 27 litres of acid, 16 kg of potash and 150 kg of other materials to make bombs was recovered. This shows the involvement of habitual offenders and professional killers; as also pre-planned nature of the riots. The habitual offenders were seeking political roles and respectability by participating in riots (Engineer, 1984, p. 272). The 1982 riots were triggered off by Temple-Mazaar controversy – a mini Ayodhya like situation. The political and religious elite of both the communities were claiming a disputed structure which the administration had locked. VHP was mobilizing the Hindu community around the demand to open the lock and allow them to worship.

The 1987 communal riots in Meerut were even more heinous and fatal. Officially, 117 persons were killed and 159 injured, 623 houses, 344 shops and 14 factories were looted and burnt between 19th and 23rd May. However, isolated incidents of killings continued until 15th June. On 10th June, 11 Muslim passengers were pulled out from buses in Meerut and killed. 68 persons were killed in Maliyana by the PAC and 40 persons were shot dead near Moradnagar Ganga Canal by PAC, all Muslims (Engineer, 1989, p. 327). In the 1989 riot, one person was stabbed and three were injured.

Although after 2014 there have been no Hindu-Muslim riots, the nature of violence has taken a new turn while the traces of its previous form are still present. Although riots still occur in India, there has been a shift in nature of communal violence after the electoral victory of BJP in general election in 2014 and the subsequent state election in Uttar Pradesh in 2017. Lynchings and other forms of mob violence targeting vulnerable groups like Muslims, Christians, Dalits, and Adivasis over cultural issues of cow slaughter or beef consumption, inter-faith relationships, and child lifting have seen an upsurge in recent years. The incidents of lynching and vigilantism were recorded in high number in Uttar Pradesh.

During our visit, we met lawyers representing the survivors of communal violence in various fora to seek justice. We talked to Adv. Sanjay Jackson, Adv. Iqbal Ahmad and Adv. Liaqat Ali Khan. Talking to them we got a preliminary impression that rather than large scale cyclic occurrence as described above, communal violence was now scattered, all pervasive and everyday occurrence. A band of aggressive Hindu extremists, apparently enjoying political patronage from highest authorities in the state and the local police, fearlessly operated targeting members of minority community using coercion and violence. They had scant respect for law and propriety. Minorities were not their only victims. Hanging saffron scarf round their neck, they freely violated traffic laws, civic laws, and muscled their way around controlling the streets and social environment. They could enter any minority home, dictate them around, accuse them of all kind of wrongdoings, beat them up and call police to arrest them and charge them with false cases. The police would oblige. They disrupted prayer meetings in Christian households and private gatherings accusing them to be meetings for religious conversions. The Muslims could be accused of “love jihad”, cow-slaughter etc. Their hapless victims would plead their innocence with the police and request them to take their complaint instead, but to no avail. In fact, that intimidating environment prevailed in the Bar as well. The chamber of the advocates we were talking to would be crowded with clients as they worked selflessly for justice to minority victims. The office bearers of the bar would taunt them and made them vacate the bigger chamber and took away half their space.

Advocates narrated us various incidents that occurred over time in Meerut. For example, on the eve of Janmashtami this year, in a Hindu colony, a young Muslim man, Afzal, and his family were attacked for ‘enjoying’ on Hindu religious festival. However, advocates elaborated the reason- that Afzal’s better sound system which he lent to his Hindu neighbour hurt the feelings of the other Hindu neighbour and was attacked for this. We could not verify the details of the incident during our visit and hope to probe further on the incident in our future visits. We share below details of one of the incidents narrated to us by the advocates to map the extent of attacks on freedom of religion or belief in everyday lives in Uttar Pradesh and nexus between right-wing organisations like Bajrang Dal and the state institutions like police.

Incident details:

Jatin Joseph and Shirish Shinde belong to “Jehovah’s Witnesses”, a minority Christian religion. On 20th September 2017, Jatin and Shirish visited residents of Vikas enclave, Rohta Road, around 10:00 AM to share good news from the Holy scriptures to those people who were interested in listening. Sharing good news from the Holy scripture forms the essential practice of their faith. Jatin and Shirish went to the house of Pawan Gupta, who happens to be member of RSS around 10:40 AM as they were both invited inside the house. During the discussion, Gupta suddenly grabbed the mobile and iPad of Jatin and Shirish. After some time, they were held captive in his house forcefully for more than an hour and were beaten with a belt on the allegation that they both were trying to forcefully convert them to Christianity. Gupta alleged that Jatin and Shirish asked him to follow Jesus and connect them to others in the locality for the same. Upon asking what the benefit was to Gupta, they allegedly told him that he would receive an amount of five lakh rupees if five meetings could be conducted at Gupta’s residence. He claimed that they showed him the video clips and pictures about Christianity on their iPad. On orders of his father, Gupta’s son called members of Bajrang Dal and Rashtroday to handle the situation. Both Jatin and Shirish were brutally beaten with sticks, and their iPad was snatched, and data was shared from the device without their consent. They tried to suffocate Jatin by strangulating him.

Only around 12:45 PM, Jatin and Shirish were taken to Kankerkhera police station, handed over to the police by Pawan Gupta and the mob that had gathered at his house. They reported to police that the two were involved in forceful conversion. Pawan Gupta made a formal complaint against Jatin and Shirish under IPC 295A, claiming that they tried to deliberately outrage and insult their religious beliefs. Gupta notes in his FIR that he called his ‘friends’ when he realised that Jatin and Shirish were trying to convert him to Christianity. Further, the FIR does not mention anything about the assault that his ‘friends’ perpetrated between 10:45 AM to 12:45 PM. Jatin and Shirish pleaded with Mr. Lokesh Kumar, police officer present in the Kankerkhera police station, to register their complaint about the assault on them by Gupta and his ‘friends’ including Balraj Doongar, member of Bajrang Dal and Dushyant Rohta. When Jatin and Shirish asked for medical treatment because of the bruises they had to suffer, police not only refused to do so but also detained them illegally in the lock-up room till the next day. They were taken for medical check-up the next day handcuffed to each other. A constable was holding a long chain tied to the handcuffs. When the medical examination, conducted at the PL Sharma District hospital, Meerut, at 12 PM on 21st September, proved that Jatin and Shirish suffered injuries on chest, back, face and hands. The advocates representing the victims also noted that the Bajrang Dal members even tried to interfere in the medical examination process.

Vigilantism as a form of domination:

Earlier scholars noted that riots in India are properly planned and executed for electoral benefits. Gareth Nellis, Micheal Weaver, and Steven Rosenzweig have earlier elaborated how riots profited the BJP electorally. After BJP came to power in 2014, nature of violence has shifted from riots to small scale vigilantism that not only keeps check on the marginalised communities from immediate vicinity but also spreads fear across the nation. Vigilantes aim to maintain the domination in public sphere by dictating terms of the social conduct. On one hand, vigilantism amounts to physical coercion on the victim’s body. On the other hand, it often results in self-disciplining of people over their conduct and remind them of their ascribed status in public sphere. Vigilantes enjoy patronage of political power that gives them impunity from the actions they commit. Perhaps, this explains why incidents of mob lynching relating to cow slaughter or beef consumption and inter-faith relationships is higher in states ruled by BJP. In fact, in the Jatin and Shirish’s incident discussed above, Jehovah’s witnesses, religion to which the victims belong, are principally against forceful conversion. They were never accused of forceful conversion before. However, the facts did not matter to the vigilantes who were pre-determined in their action. Further, it is interesting to note that while Gupta claims that Jatin and Shirish happen to induce him to convert to Christianity, but an upper caste Hindu family in good locality will not be ideal household for that. It appears that Jatin and Shirish were, in fact, trapped by Gupta who is well connected not only to Bajrang Dal and Rashtroday but also to the police who refused to register even a complaint against him when asked by the victims. Further, the ecosystem created by the BJP for vigilantes to thrive gave Gupta and his ‘friends’ to not only attack but hand them over to police and charge them with false allegations.

Police and vigilante nexus:

The motto of Uttar Pradesh police- “Surakhsa aapki, Sankalp hamara” translates to “Your protection, Our Pledge”. However, the Police in the BJP led government in Uttar Pradesh has resorted to partiality when dealing with cases related to mob violence. It appears that the police’s protection is not equal to all citizens and some sections of the society enjoy the right to dominate and silence the minorities. We were repeatedly told that Bajrang Dal leaders and members often get away with their actions unchallenged. It was found in our investigation that police played a dual role in such instances. On the one hand, the police often collaborated with the right-wing organisations in such incidents. In the incident mentioned above, police not only failed to register the oral and written complaint of Jatin and Shirish against Pawan Gupta, Balraj Doongar and Dushyant Rohta but also subjected victims to inhumane conditions by illegally arresting them and subsequently parading them handcuffed as criminals. There was no probe into the injuries sustained by the victims at the residence of Pawan Gupta. Police also shamefully claimed that they are arresting the victims for their own ‘safety’. On the other hand, there seems to be pressure on the police machinery from the state to book more cases relating to conversion and cow vigilantism. The state apparently incentivized booking of higher number of cases of “religious conversions” and “cow slaughter” targeting Muslims and Christians. The vigilante-police nexus thus worked to the advantage of both. Advocates representing Jatin and Shirish mentioned to us that the police also complained of pressure from the government when they demanded released of the victims.

Conclusion:

The above incident presents us the case of normalisation of vigilante behaviour and impunity they enjoy. The presence and misuse or of laws on marginalised communities seem to one of the factors that gives the moral right to the vigilantes in coercive practices. Further, the institution of police failed to not only protect the victims who are assaulted but they are also legally punished for offences they did not perpetrate.

References:

Brass, Paul R (2004), “Development of an Institutional Riot System in Meerut City, 1961 to 1982”, Economic and Political Weekly, Vol. 39, issue 44, pp. 4839-4848.

Engineer, A. A. (1984). An Analytical Study of the Meerut Riot. In A. A. Engineer, Communal Riots in Post-Independence India (pp. 271-280). Hyderabad: Sangam Books.

Engineer, A. A. (1989). Communalism and Communal Violence in India: An Analytical Approach to Hindu-Muslim Conflict. Delhi: Ajanta Publications (India).

Engineer, A. A. (2004). Commual Riots After Independence: A Comprehensive Account. Delhi: Shipra Publications.

Varshney, Ashutosh and Wilkinson, Steven I (1996), Hindu-Muslim riots 1960-93: New Findings, Possible Remedies, Rajiv Gandhi Institute for Contemporary Studies, New Delhi, pp. 27

Wikipedia (a). (2021, October 17). Meerut. Retrieved October 21, 2021, from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meerut

Wikipedia. (2021, July 10). Meerut (Lok Sabha Constituency). Retrieved October 21, 2021, from Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meerut_(Lok_Sabha_constituency)